An Englishman, an Frenchman and a German get on a plane to the Arctic. It’s like the start of a bad joke.

(above photo borrowed from T.)

Nose pressed against the aircraft window gazing down across the glaciated mountains and sea ice now illuminated by the first glints of the midnight sun, the enormity of what we were about to do started to sink in. Amongst all places on earth, its a hard task to find more than a handful that are less forgiving than here. Bitter wind, gaping crevasses, 20 below zero, constant risk of avalanche, and all in the back yard of one of the few predators on earth who consider humans as food. Everything here is trying to kill you.

Our stated plan, was to cross the Svalbard Spitsbergen icecap by ski to reach the abandoned Soviet mining outpost of Pyramiden on the north side of Billefjorden. It’s a fascinating place. It was originally founded by the Swedes at the turn of the century in the big Arctic coal boom, and was sold to the Soviet’s in 1927, where it became a kind of statement piece to prove to the world that the great Soviet Union could create a thriving community in some of the most inhospitable terrain on earth. They even flew in tones of soil from the Caucuses to allow them to grow grass here to feed the hundreds of cows they needed to cultivate to get fresh milk and meat for the residents. Unlike many cities of the Soviet era, it was open to the West and visitors were actively encouraged. This meant that as well as being the beneficiaries of high wages and top-class infrastructure, the citizens of Pyramiden were supposed to behave in a way that embodied the communist ideal. Everybody ate together in a communal kitchen, were expected to be part of a theatre group, or play an instrument, or play in the sports teams (I’ve no idea who they played against…). Amazingly, it lasted until the late 90s, well after the collapse of the USSR, where the custodians of the town ‘ArktikUgol’ (the Russian arctic coal mining company) decided that with the removal of the socialist government subsidies, enough was enough and pulled of the vastly unprofitable endeavour. The intense cold up there means nothing really decays, and the remains are one of the best preserved examples of a Soviet era town in the world.

These days, you can go to Pyrmaiden on a tour, but by making the 90km journey under our own steam we’d hopefully save ourselves a few quid, learn a bit more about what it takes to exist in these extreme conditions and have total free reign around the town when we got there, especially with respect the vast coal mines on the south facing mountain side that overlooks the now deserted city. With a snowmobile drop off from Longyearbyen at the head of the glacier, we estimated it would take us 3 and a half days of skiing to make Pyramiden, with one full day in the town and a further half day to ski 7 klicks south to the edge of the frozen sea where we were to be extracted by icebreaker and taken back to Longyearbyen for a beer and burgers.

The pack-out for this one was a bit more involved than the usual. Layers and layers of cold weather gear, 7 days worth of food and cooking gas, ice axes, crampons, crevasse rescue gear, avalanche transponders and probes, an expedition tent, satellite phones, flare pistols, 2 large calibre rifles and a trip wire system for polar bear defence, all loaded on to 2 pulkas so we could drag it across the ice on our skis. The danger of bear attack here is extremely real, and it’s actually illegal to leave the settlement of Longyearbyen without a means to defend yourself. With the right paper work, you can easily rent yourself a weapon on Svalbard, although your milage may vary. The Mauser ‘98s we had managed to pick up were absolute antiques, still bearing the nazi Reichsadler from their days in service back in the second world war.

To make sure the things still actually worked, we had to plink a few rounds of 30.06 at the Longyearbyen gun range, an old horseshoe shaped quarry in the the hillside that overlooks the airport and the famous seed vault. We grabbed a few bits of metal plate that were laying around and set up a target at the sort of distance you’d want to start shooting if an 80 stone polar bear were charging at you. After confirming they actually shot straight (and they weren’t bad considering their vintage), we created a few drills to test ourselves – running to an unloaded gun on the floor and trying to load and fire it with thick gloves on, marching up and down and having someone randomly shout “BEAR!!” and you having to put 5 rounds on target as quickly as possible. With about 7 layers of clothing and thick gloves, this really took some practice, and it was a while before all of us felt comfortable handing a rifle, quickly when dressed like the Michelin Man. Rifle practise, or lack thereof, was a serious contributor to the untimely death of an English public school boy on a trip here in 2011, and it was one thing we really wanted to dial in and get second nature. Another thing you’ve got to worry about is snow getting in the action or barrel when you’re reloading. Wet bullets are not the end of the world, but they can cause you problems with weak fire and excess pressure on the bolt, ice in your barrel however, can be catastrophic. It can literally make your barrel explode. To alleviate this risk, we borrowed a trick from the special forces – trying the finger of a latex glove (or a rubber johnny if you’ve can’t get one of them) to the end of the barrel. It won’t affect the shot if you have to take one, but it will keep all the crap out the gun. The other thing you can’t do, is keep the guns in your tent. Condensate will very quickly form in the barrel and turn to solid ice as soon as you take it back outside. Then you really are stuffed.

Longyearbyen, the departure point for our endeavour and pretty much the most northern settlement in the world, is a strange town indeed. The omnipresent wooden pylons of the old coal gondolas that crisscross the hillside ensure you’re never too far from a reminder as to why anyone would want to build a town in such an unlikely place, but with only 1 mine still left open solely to provide coal to the power station, things here are really changing. The former coal mining hub is having a good go at reinventing itself for the age of mass tourism, but it doesn’t seem to have been as well marshalled as the literature would have you believe. Many of the locals, mostly former miners and their children are a bit pissed off that their once quiet corner in the high arctic is now too expensive to live in with all the homes turned into Air BnBs and the streets constantly buzzing with tourists on snow scooters. Everywhere you go, the signs on the shops, pubs and restaurants remind you where you are with a picture of a polar bear and 78˚ sign, and it gets pretty old, pretty fast, even for a visitor. The locals must have had it up to their necks.

The 2 days preceding our departure were mostly occupied with fixing supplies, equipment and transport services (there isn’t much else to o here in any case), but we managed to get a quick look in to one of the ancient mines way up on the hill side, donning the crampons and ice axes and hacking our way up the snow and ice, the evening before our departure.

I was half expecting to be able to get in to these mines themselves but the century old adits were either collapsed or completely full of ice and frozen earth.

Still, there were a few nice bits and bobs lying around.

The next day, on 4 hours sleep, we met our 2 drivers who would get us out to the ice cap. Taking three snowmobiles, me driving one and them taking the other two with X and T riding pillion (with a plan for the drivers to tow the third machine back from the drop point on the sled trailer), we hit the tracks, flying up the valleys of Spitsbergen to the Rabot Glacier to begin our journey across the icecap.

Have a Good Trip!

Before buzzing off in to the distance and leaving us to it, one of the snowmobile drivers pointed out some distant figures on the horizon pulling pulks, maybe 6 or 7 km away.

’It looks like you have company. Strange to see someone out here at the moment’

I wondered who on earth was a daft as we were, but they were so far away I thought no more of it. 2 minutes later, the snowmobiles buzzed off in to the distance, and with the 2 pulks loaded and attached to our harnesses (we’d have two men pulling pulks and one on rifle duty), it was time to get on with it.

The plan, borrowed from an antarctic expedition report we’d read from a few years back, was to ski for 50 minutes, stop and eat a small snack of cheese, or meat or something for ten, rotate rifle duty and repeat all day. The idea is that you don’t have to stop for big lunch breaks, you never hang about so much you get freezing cold, and you get nice regular rests.

We learned quite quickly where our problem points were going to be. For the most part the skiing was straight forward, literally. An endless frozen trudge, one foot in from of the other, mile after mile, punctuated every 50 minutes with the obligatory rest stops. These stops almost never ran to time. We were still finding our feet with this stuff and so as well as the snacking there was endless faffing about with gear. Adjusting pole height, faffing with bindings, getting cameras out.. It wasn’t these delays that really caused us so much stress though, it was any time we encountered a severe downhill gradient.

The pulks, missing the rigid aluminium pole attachments you’re normally supposed to have for these sorts of things just flew past us like massive orange run away dogs, slowly overtaking us as we both tried to regain control before getting ahead of us completely and tangling us up in our tow ropes, bringing us crashing to the ground in a tangle of gear. It didn’t help that none of us had any experience whatsoever with nordic style telemark skis. Normally, when I’ve been in these situations before I’d had dynafit style bindings and big touring skis. Get to a downhill? No problem! Lock your heel in and carve it up like a tourist in Chamonix. These Nordic things, with their total lack of both edge and surface area were absolute uncontrollable death traps, especially when you consider the permanently locked toe binding which could have easily contributed to a broken ankle with the wrong sort of fall. It took us longer to drop down a 400m decline than the 3km that had led up to it, and things were getting ridiculous.

X created an ingenious braking system from a sling and a pair of carabiners that would get caught underneath the pulk and drag underneath it, slowing it down whenever it started to run away. I’m sure any Norwegian worth his salt would have found this hilarious, but it totally saved our bacon.

Towards the end of that day, we began to catch up with the characters we had seen on the horizon 7 hours previous. By their tracks it looked like there were 4 of them, and they had at least one dog. It also looked like they had started to set up camp around 4km ahead of us at the current high point of the glacier.

“Shall we just go up and say hello? If they’ve got a dog we might actually be able to camp together and skive polar bear watch this evening and all get some sleep?..”

The one major pain in the arse about camping in polar bear country, is that you can’t just go to sleep, well, not if you’ve not got the right stuff. Ideally, you want to have one man awake at all times to make sure you’re not going to get eaten (for every bear attack in recent history: there was no bear watch). As a backup, you should set up a tripwire system in case the man on watch falls asleep or a particular crafty bear wants to sneak up behind. What a lot of people do who want a good nights kip, is get a husky. Huskies are good because they’ll smell a bear a mile off and bark like mad. This means you can all go to bed without too much worry. They’re also happy sleeping outside the tent in -25 degrees and will even help pull your pulk along on the ice.

So with this in mind, we kept going, now following their tracks towards their camp on the horizon.

‘Hallo!’

We neared, and two of the men walked from their camp toward our path with the dog. I don’t know if they were just taking the dog for a look for its own benefit or if they actually thought we might be a threat and needed something to give them a hardman of the ice look, but they were probably just as surprised to see us out there as we were to see them. We quickly exchanged pleasantries and our request for a camp-share was gladly accepted. They turned out to be a bunch of thoroughly top blokes, much older than we were, way more experienced, and amazingly, doing a very similar route to us over the glaciers towards Billefjorden.

Their camp was a decidedly less-amateur affair when put up in direct comparison to ours, even with our posh-tek Hilleberg expedition tent. Unlike our bear tripwire system, a military surplus kit for forest warfare now held into the snow with skipoles and a prayer, they had a more better looking, obviously purpose built rig: ultra sensitive hair-triggers, held into the snow with big wooden steaks that actually looked like it would do the job. They had also dug their tent porch section 2 feet down so they could all sit properly round their stove and hang out in the relative warm, had brought big flasks of this gorgeous forest fruit liquor and were cooking bacon or something on thier roaring petrol stove.

us…

..and them

When we came to cook, we quickly found out why you don’t take camping gas and a jetfoil out in temperatures of -25 and below. The gas had frozen solid in the can. If we couldn’t solve this we were absolutely fucked, as we wouldn’t be able to cook or even melt snow for drinking water.

The best we could manage out of our pathetic ‘super duper MSR winter gas’ can was a tiny flicker of flame after shaking it up and down like mad and putting it inside our jackets for 20 minutes. Nothing was boiling. It was barely even melting.

The solution to this little predicament was inspired.

“why don’t we cook the gas before we cook with it?”

We loaded one gas canister on top of the other stove, got the tiny flame lit and started to melt the frozen condensate inside the second can. The other expressed their reservations about such a tactic, but I wasn’t too worried. I’ve had plenty of experiences in my youth of throwing these fuckers onto burning bonfires, and I know full well it takes a good 15 minutes at 1000˚C for them to explode (in a glorious bright white and orange mushroom cloud incase you were wondering). Down at -25˚C, with this amount of flame, we could have cooked the thing for 6 weeks and not had any bother.

It was amazing how quickly this tactic worked as well, and before long we were cooking with gas. (lol).

The Norwegians left us the next day with a friendly warning:

‘There is a lot of wind tonight, we will be making camp early. Be prepared’

By the time we set off, the visibility was already terrible and proceeded to get worse throughout the course of the day. Considering the massive distance we’d managed to pull off the day previous, we essentially gave up after a paltry 10km and decided we should make camp early in the increasingly savage wind. Without the blessing of the dog, we were out on our own for this one and three- three hour shifts of polar bear duty, stood in your down trousers clutching a frozen rifle and staring out into the infinite white out was going to be the order of the night. We were going to draw straws for who had which rotation, the shitiest obviously being the middle one, 3 hours sleep, 3 hours up, 3 hours sleep, but no one seemed too fussed about which one they got. I took the first go, X was up second and T was on the breakfast shift.

In those circumstances of total sensory depravation, we all reported having hallucinations, X seeing random mountains appearing on the horizon and me seeing tiny white dots in-between all my frantic movements to try and keep warm. Just pacing up like a cartoon soldier worked for a bit, but the close confines of the bear alarm trip wire system we’d set up didn’t allow for much more exciting than jogging-on-the-spot, star jumps, and a busting a casual bit of disco. Hopping up and down on the spot and doing the Saturday Night Fever dance with a loaded WW2 rifle at 3am on a Tuesday morning, I’d have forgiven any hungry polar bear for assuming we’d all got new variant CJD and given us a very wide berth indeed.

The next day was glorious, and we set out in good time in amazing weather.

“What are those weird lines on the snow?”

“…Shit. Stop. Let’s get the ropes on.”

A crevasse is a huge fissure in the ice, cause by the slow movements of the glacial ice. They’re often covered by bridges of snow and have been the cause of many a death and injury to the unprepared. On a set of skis, you’re a little bit less likely to plunge to your icy doom than you would be if you were just walking, but that knowledge isn’t that reassuring when the sound of the snow changes as you move over it. One second, it sounds solid, like the regular tightly packed stuff we’d been skiing over for the previous 3 days, the next, it sounds hollow, and you try to shuffle on quickly over the enormous precipice you’re undoubtedly standing on top of, supposed by a couple of feet of snow. The thing is though, you can’t shuffle on quickly, as if you’re doing it right you’re all roped up and all have to move at exactly the same speed, which is the speed of the slowest man in the group.

A fall into a crevasse here would have been interesting… Our ice axes were all slung into the straps on our back packs to be as ‘quick-access’ as possible, but because we needed our hands for the ski poles any incident of a disappearing man would have to be dealt with by the other two just falling over in the snow and trying to grab on to the ground for dear life, hoping the rope between us saved the man who’d just taken a trip downstairs and not pulled everyone else in after him. What the pulks would have done in such a situation was anyones guess, probably tumbled in after the unlucky fellow dangling on the end of the rope, smacked him on the back of the head and if he was unlucky, strangled him on the tow ropes. This is before said unlucky fellow realises that the snow he’d just fallen through to reach bottom of said crevasse has now collected around his skis and half buried him, which he would have been completely unable to escape from due to the non-quick-release nordic bindings. It was best not to think about it.

There She Is!

On the other side of the crevasse fields, and from the top of Nordenskiöldbreen, we could now make out Pyramiden, 20 or so miles away down the glacier and across the frozen sea ice on the north bank of the fjord. The decent looked incredible, 15 miles of perfect gradual slope between the towering sides of the valley at just the right gradient to cruise down with the pulka sailing behind.

It was indeed, nothing short of perfect, and we arrived at the foot of the glacier a couple of hours later, stood on the first part of the sea ice and staring up at the jaw dropping bright blue seraccs with the occasional sounds of the glacier popping and creaking and cracking under its own gargantuan mass.

It was 11pm, and the sun had finally dipped below the mountains by the fjord. It wouldn’t be getting dark, but it was late and getting extremely cold. If we’d have been on top of the glacier we’d have probably have camped, but down here on the sea ice, the same place that the bears live and eat, we didn’t really have that option. The only real choice was to ski 8 miles north towards a headland jutting out into the ice where if our map was correct, stood an old wooden hut we could hopefully barricade ourselves into.

There is nothing more to say about this last section, apart for the fact it was a horrid slog. We’d been skiing for about 14 hours by this point, we were all ruined, and the sense of elation was palpable when we made it to those huts and found the door open.

By this point we were ahead of schedule and only had another few miles to go. Pyramiden, directly across the flat sea ice from our current position, would only take around 2 hours to get to so we could afford a bit of a rest day. We had a bit of a lie in, and spent our time chilling out and lounging in the sun (it was an absolutely roasting -5 degrees), eating, sorting our kit out and cleaning out the ice that had accumulated in the rifles from our crossing.

When time came to set off, we made a direct line across the frozen sea to our first port of call: The abandoned power station.

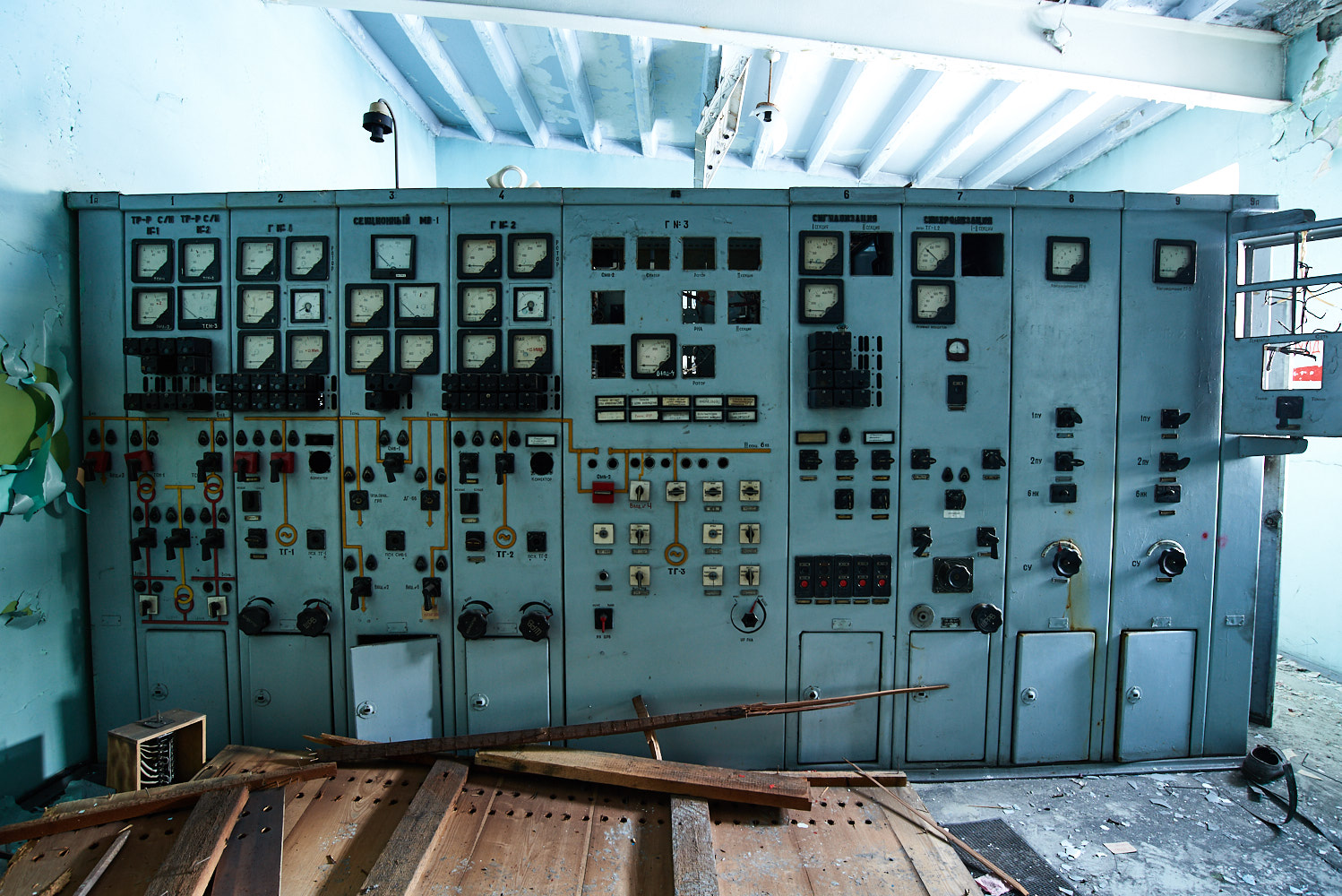

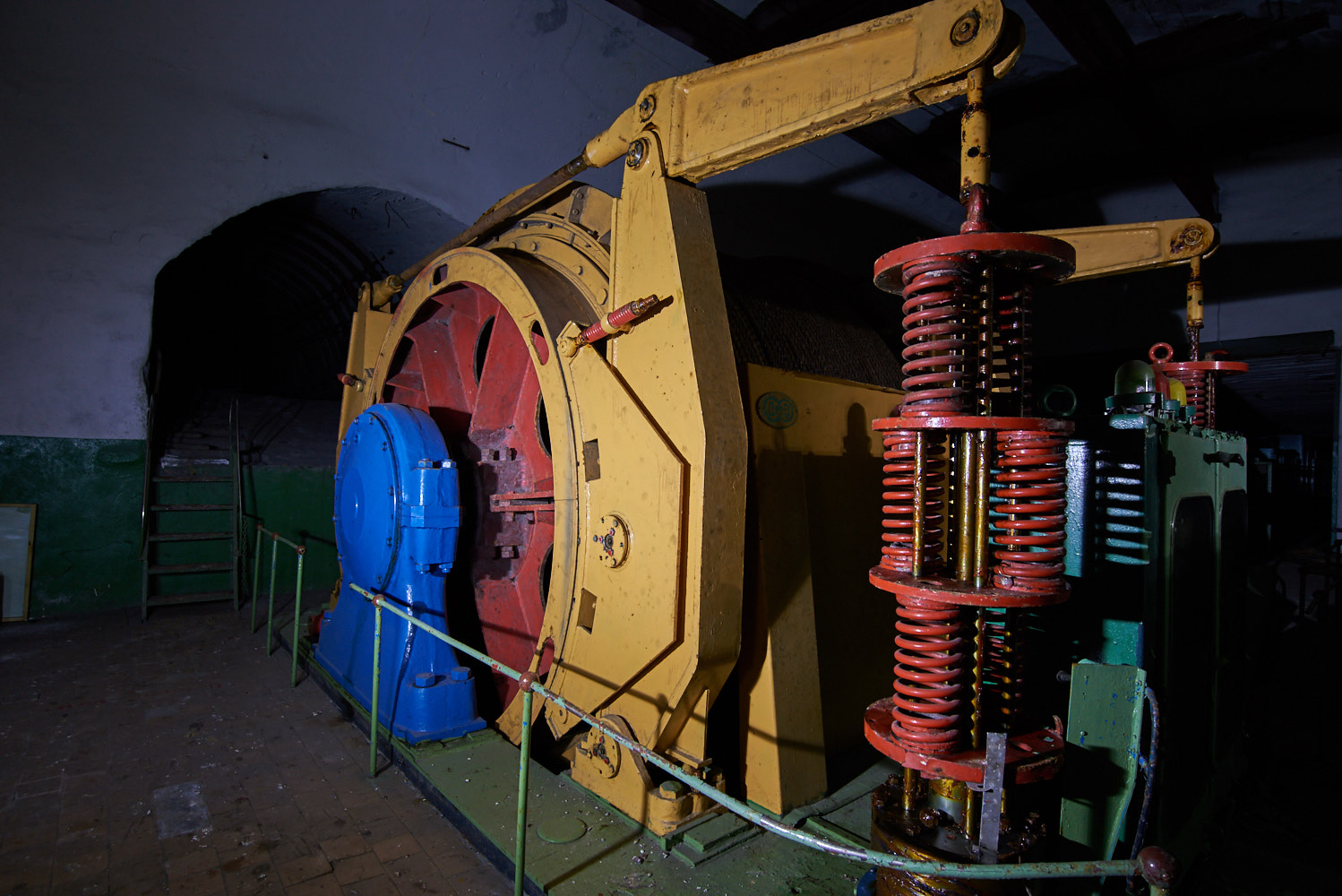

I had high hopes here: Dreams of 1950s era soviet turbines and untouched control rooms, and I have no idea why. Like most other things that embodied even a smidgen of value in the former soviet union, they had been stripped to within an inch of their lives, the turbine hall being nothing more than an empty shell containing the upturned housings of the long-since removed generators.

Still, there was plenty of other weird and wonderful things still remaining.

The basement here was encased in 2 feet of solid ice. Nothing escapes it.

Leaving the power station around 3am, we needed a place to sleep. It would have been too much of a ball ache to lift all our gear in though the tiny side window we had managed to crawl though to get in, so we needed something more suitable. On the way into town, we came across a set of bear tracks, two cubs and a mother, and were approached shortly after by two Russians on snowmobile. Their uniforms bore the logo of the ArktikUgol company, and they were out on bear watch, looking for any that might be approaching the settlement.

They instructed us to go to the ‘Hotel Tulip’, the latest (and only) tourist accommodation in town, providing rooms for the handful of workers and the sporadic stream of tourists that come here on their snowmobiles and boat tours in the summer. At 3am, we weren’t too sure there’d be anyone around to let us in, and besides, with all the kit we’d had to rent/buy, we’d already shelled out more Kroner than any of us were really happy with, so we hauled our shit into the most solid looking abandoned building we could find, barricaded the large steel doors and got a brew on.

The next day we hid the gear in our new base and hit town. The first thing we passed was the famous red and blue sign by the docks, erected on the 30th or 40th anniversary of the town as a grand welcome to anyone coming into the town by boat, with the last ton of coal extracted from the mine left in a cart next to the sign. Most of the buildings here have been ‘sealed’ to stop roving copper thieves and souvenir hunters from twocing all the cables and soviet memorabilia, but they’re only really secured against normal people. If you’ve got a decent box of tricks up your sleeve you can go where you please without having to break anything, and we set about exploring the ‘famous’ bits.

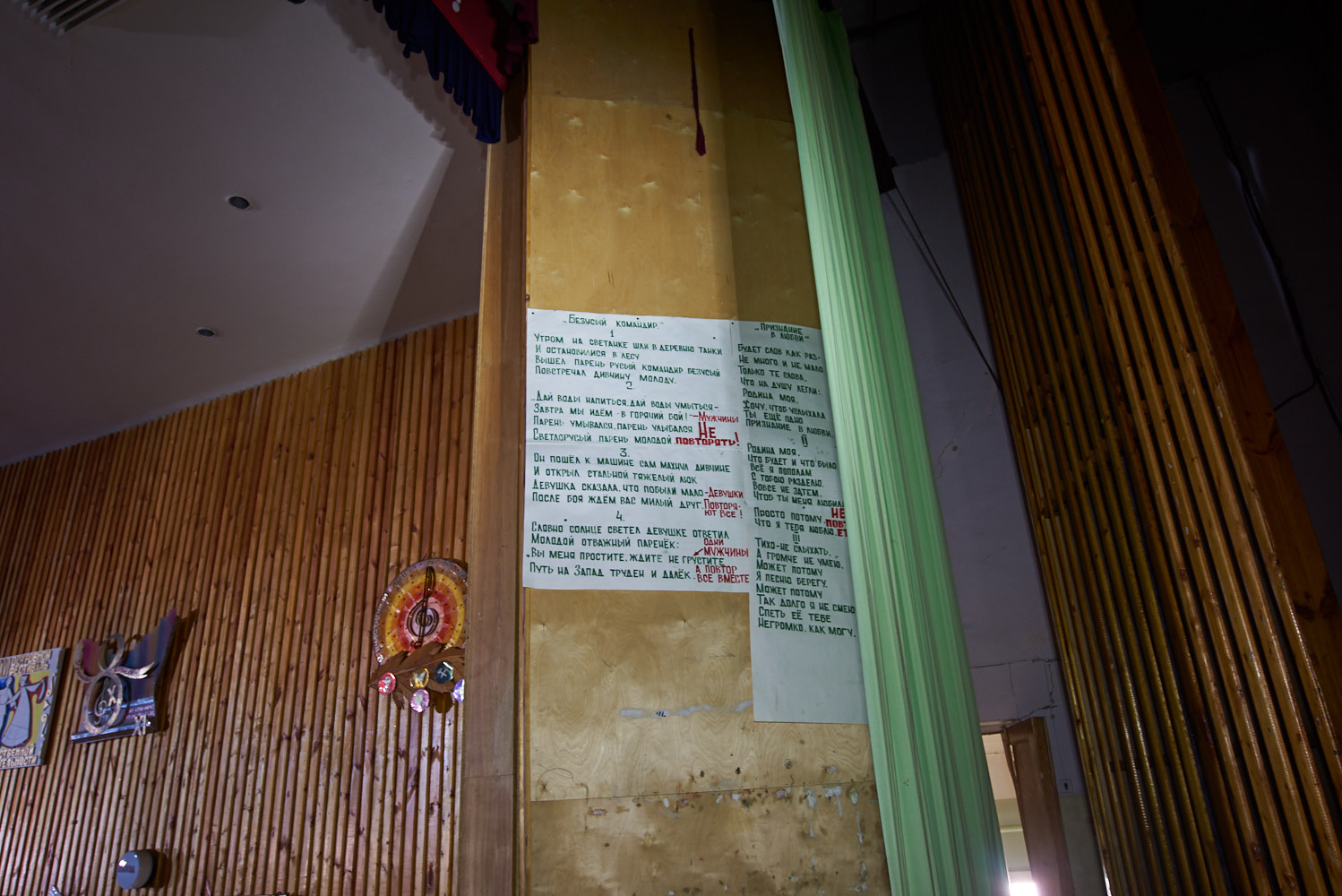

Pyramiden was supposed to be a model embodiment of the Soviet ideal. A perfect community on the edge of the world where everyone played music, stared in the community plays and were members of the sports teams. Few of the houses had kitchens. Everyone was expected to dine together in the central canteen, A huge hall emblazoned with an old soviet mural of Baba Yaga and a bunch of polar bears hanging out on the sea ice.

There are a few interesting sports facilities, and I’m presuming this is the most northernly swimming pool, basketball court and massive frozen-pipe based sewage pipe turd explosion..

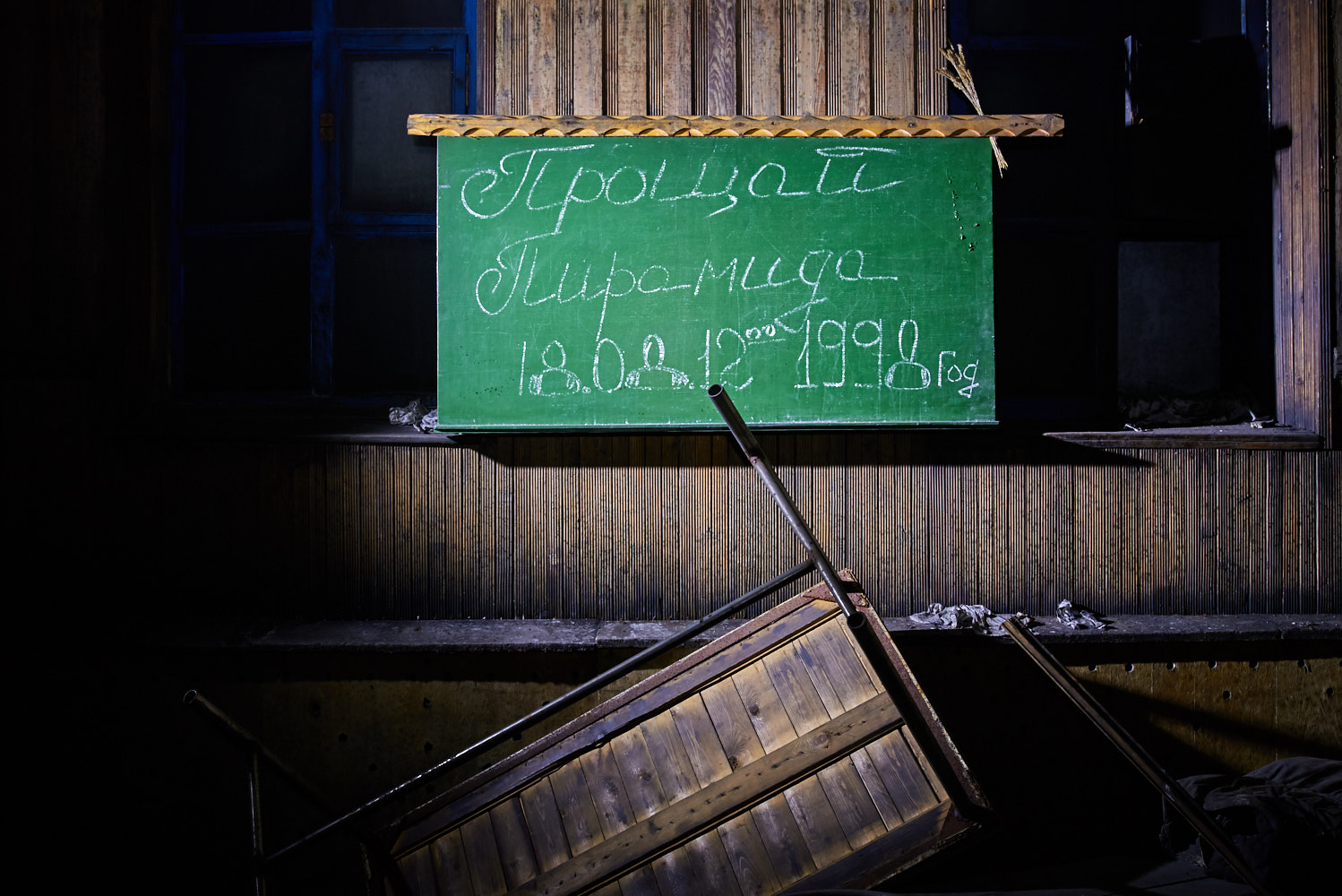

In the auditorium, sits the worlds most northern (and hideously out of tune) piano. An old Red October on the main stage of the concert hall and cinema, below the last words of the last song of the last play that was probably performed here.

We gave the hotel a visit. The food and beer was cheaper than we thought.

“You ordering a beer?.. It’s like 3pm”

A short Norwegian girl in a tourist-guide uniform hollered up from her almost totally reclined position on one of the hotel lounge arm chairs.

“Yeah…” I replied. “We’ve just flippin skied here, and anyway it’s the most Northernly pub in the world. I’ve gotta get at least have one pint in”

“It’s not”.

“..What..?”

“There is another one now” she retorted smugly. “In Ny-Ålesund”

I didn’t really have a decent comeback.

“Well I’m bloody not skiing there!”

Party at Mine

3 hours and a hundred quid later, we emerged, pissed, into the still bright evening. This midnight sun and total lack of darkness was really messing with my head. I felt knackered from all the interrupted and short sleep but didn’t feel in any way sleepy – the only darkness we stood a chance of getting was underground, and we started our 2km ascent up the side of the mountain on the 35 degree slope incline.

They must have used a whole forest to make this thing. A stilted mile long coal funicular, made from hundreds and hundred and hundreds of tree-sized beams. Only the Russians could have busted something like this out. It was a gruelling ascent, and one I’d not like to repeat anytime soon. The gradient was bad enough, but with all the ice that encrusted everything there, you were permanently 2 seconds away from slipping on an ice slope and tumbling down a bunch of frozen sleepers.

On reaching the top, exhausted, we crawled and crashed our way through the walls of ice that had formed at the entrance, and began a climb go yet another enormous tunnel into the mountain.

You can’t quite see it in this photo, but that yellow shit is frozen solid and was absolutely lethal. There were a few close calls that almost ended in total disaster, as if you weren’t careful there would be nothing to stop you flying down the hyper steep incline and smashing into the ice wall at the bottom at about 40 miles an hour.

Soon though, we arrived at the personal station. Two rows of perfectly preserved benches and the last shift card still nailed to the wall.

We set off into the mine.

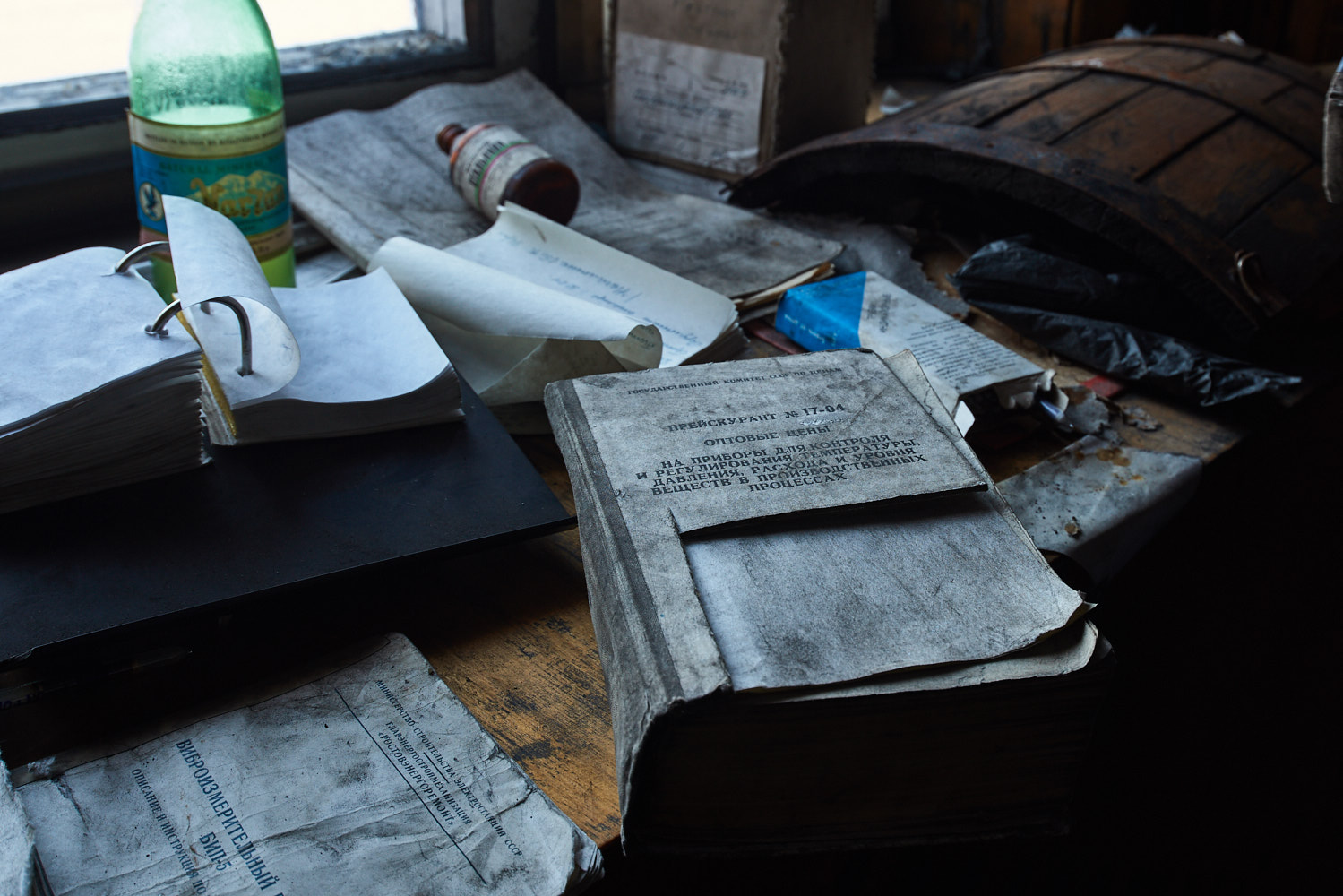

It had been an enormously long time since I’d been somewhere as perfectly preserved as here. With no wind, damp (all moisture turns to ice) and a constant -10ish all year round, nothing decays. The only form of natural destruction here is there permafrost, and that eats everything. You can see it growing our of the walls, and floors causing collapse after collapse in most of the workings we explored. Huge crystal ice formations and log books signed with by the last shift manager on the last day of working still sat on the tables around the place.

We were in there for hours.

On leaving the mine we had roughly 4 hours to get some sleep, pack up and make our way south across the ice to meet the icebreaker that was going to take us home. We had managed to contact the boat by satellite phone and been given pickup location and a 12 noon deadline, so it was another early start for our last ski across the sea ice.

As it happened, the Norwegians we had seen on the ice were being picked up here also, as well as another chap, Adam, who we met on the edge of the ice, a Polish photojournalist who had been out there for 5 weeks on his own, living in the wooden huts by the sea ice and photographing polar bears and birds for his book on the decline of the arctic habitats.

It was a lovely end to the trip, and we sat about nattering on, sharing the last of our food tea and whisky, and comparing note on our respective trips.

Extraction.

The ice breaker came into view.

“Urrl”. Adam grumbled.

“Bloody millions of tourists”.

I had a good look though the monocular, and sure enough, there were about 20 people hanging off the side of the ice breaker with their dSLRs on flash-mode, presumably wondering why the nature cruise they’d paid for was being diverted to pick up 8 lone souls stood on the ice in the middle of nowhere.

With the pulks on and rifles unloaded and surrendered to the ships captain, we hopped on board and were transported back to civilisation, smashing through the sea ice and trying to answer ridiculous questions from the scores of confused tourists about who we were and what on earth we were doing.

Since returning from the frozen wastes, I’ve still not regained the feeling in the end of my left toe, and the obliterated skin on my hands has only just sorted itself out.

Well worth it though.

Over and out. What a belter.

Consistently THE BEST write-ups in the game. Must’ve been a real experience to remember. Always look foreword to your posts

Cheers

Cheers man! Yeah was an absolute mission.. Not sure whats next, but I think all this extreme environment malarky has got legs..

Just found your website and having a bit of a trawl through your stories etc, they are absolutely belting. You write really well and capture the nature of the trips really well. This is one of the highlights so far along with the Russian space program. Anyway, from a complete randomer to another, I hope you’re still having fun and knocking about on the many rooftops of the world.