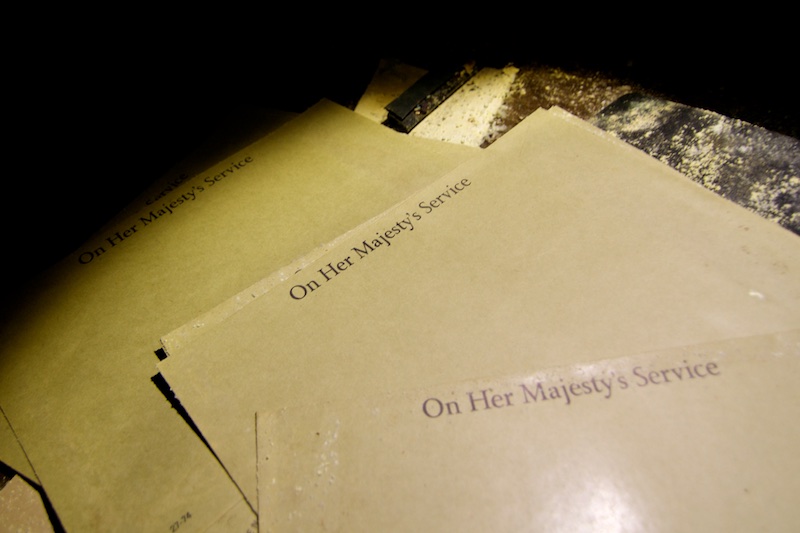

The UK’s cold war legacy is, I think, strangely unique. Not in the specific physical instantiation of the tunnels, bomb shelters and bunkers (although there are obviously differences to the constructions of the other cold war nations if you want to geek about it), but in the perfect sweet spot in which they sit, both in terms of their physical state and the lofty mantle they occupy in the minds of hundreds of thousands of now-adults brought up on James Bond, War Games and Gerry Anderson. More practically, you can attempt to access many of them without the risk of being shot, which can’t be said of the still paranoid and well funded military installations in the USA or Russia. They’ve also been properly looked after and largely, only given up within the last couple of decades, so unlike the government bunkers you’re likely to find in the former soviet union, the leccy still works, they’re not flooded and they haven’t been pickeyd to within an inch of their life.

Q-Whitehall, Kingsway, Anchor, Guardian, Pindar, Drakelow and the like. All at the top of the visit-list, not only for the fusty sub-brit tunnel bashers and wannabe action man urbex0rs (thats me btw), but for pretty much every kid in the United Kingdom who grew up in and around the supersecret-hush-hush-‘what-they-dont-want-you-to-know’ Cold War.

Burlington, Subterfuge, Stockwell, Chanticleer, Peripheral, Turnstile, Site 3.. The number of codenames for the UKs Emergency War Headquarters should give you an indication of its James-Bond rating. For those who don’t know/who’ve not opened a Wikipedia tab yet, its a huge underground city built in a disused stone quarry underneath an unassuming MOD base near the town of Corsham, Wiltshire. It was originally designed to be the central coordination and evacuation point for the government in the event of a nuclear war, and was able to safely house up to 4000 people for 3 months. i.e. – its massive, and comes complete with its own mass catering facilities, an underground lake for drinking water, a BBC studio and a telephone exchange that was the second biggest in the UK when it was installed. Impressive, yes, but its useful life was laughably short. By the mid sixties, the Soviet Union had developed the H bomb and the ICBMs to carry them, which would have gasmark 9 millioned every living thing hiding in Burlington in less than a second.

Never-the-less, it was kept on for an astonishing 30 years as a decoy site to make the Russians think there was something interesting there, although I don’t really know why. They had enough nukes to just vaporize the entire nation 1000 times over – the whole bloody country was basically just a decoy site for the USA.

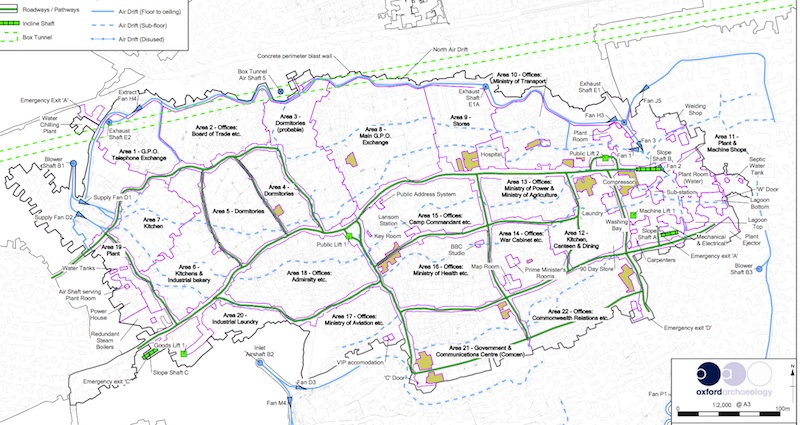

Top Secret Underground Base Map. (obtained by top secret underground googling)

Spring Quarry, the underground quarry which Burlington was built in, is actually a part of a much larger complex of quarries and mines, which pretty much got whole-sale appropriated by the MOD in the 40s. The sprawling Box limestone quarry was an exception to this mass land grab, and has long been a quality PG-rated day out for anyone wanting to dabble in underground related funtimes.

The Cathedral, Box Mine

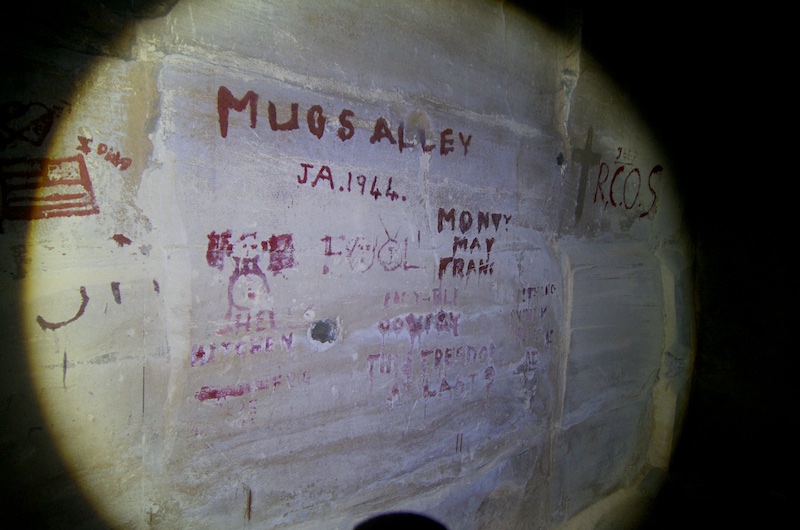

It’s centuries old, and many a jolly mine explorer have traipsed its ancient passages in search of the few historic curiosities – the old cranes and 200 year of drawings on the walls of it’s thousands of galleries. If you look on the eastern section of the map though, you’ll notice a bit simply marked ‘Grille: No Entry’, and if you venture down to see what all this is about you’ll come across an old grill and some long-since snipped though coils of barbed wire.

photo borrowed from edgecity – w/permission

This marks the start of the once classified MOD section of Box quarry, and it’s a spiffing adventure for the kids crawling through the now rusted grills and past the retro barbed wire. Eventually, you’ll end up on an expansive roadway of reinforced concrete big enough to drive a fleet of lorries down and you’ll start to feel the hum of the ventilation fans buried deep into the adjoining walls. A saunter up the road will lead you to to the famed Red Door, which marks the definite barrier to the secret world of the MOD Corsham underground.

photo borrowed from edgecity.

I would never have thought the direct route would have worked to be honest, and though I’ve not heard it first hand, the story goes that a couple of lads found out that mine surveyors working on behalf of the MOD were out walking round the mine from 9-5 in the week, and all you had to do to get into the famed bunker was wait behind a rock and jog into the open blast door which they were using to access the mine. Almost too good to be true isn’t it? Now, I’m pretty sure that the other parts of the MOD-owned Spring Quarry must have been subject to unauthorised cheeky monkeyism before this, but this was the first time proper pictures had managed to filter into the wider scene, and, as you can imagine, it stoked a few people up.

This is where it started getting silly.

Just knowing that it’s possible is enough.

As I said before, if normal people in the UK generally have a passing interest in ‘top secret cold war shit’, it’s resident explorers are fanatical.

Over the next 2 or 3 years, the battle for access was like nothing I’d ever heard of. Entire walls were demolished from adjoining mines, surface vents were cut to pieces and blast doors were gas-axed in half in a war of attrition with the MOD who were desperately patching and repatching the endless torrent of damage to their supposedly secure military facility and trying to catch the little fuckers who kept causing it.

Demolition in progress

A great many people got in and saw it first hand, some were arrested, and a few ended up hated by everyone for talking about the ifs, what’s and hows on the internet. Emotions ran strong. The Corsham Underground wasn’t the MODs, it was the property of a select group of urbexers, and woe betide those who opened their trap to the outside world and gave up their knowledge without permission..

Private Property

You can see the results of this struggle dotted all around the local area in the form of the numerous patches and re-patches of the vents, emergency exits and grills that litter the woods and side tracks all over the area, and it was this short lived period of insanity that almost certainly led the local explores who’d figured it all out, to completely close off to the outside world. Corsham was theirs, and anyone who wanted to see it first hand apparently had to make friends.

cut and paste

I suppose that this is where I entered the story.

I always find it astonishing, that there are two layers of completely unconnected networks of people who access and use our infrastructure, for completely orthogonal purposes. The people who are ‘supposed’ to be there, who generally tend to maintain or use these places as part of their work, and the people who feel they own it through the information they hold in their heads and use it for pissing about in on weekends and winding up other like-minded people through their superior knowledge of access. I wasn’t too concerned with either of these groups really, it just looked like a decent slow burning puzzle to keep chipping away on when I had a bit of spare time.

Over the course of a about a year, I’d visited the mines of Wiltshire a handful of times for a bit of mine exploring and for the excellent parties thrown in the plethora of underground spaces down there. Most of these times, I’d used the opportunity to have a good walk round the fields and public woodland around MOD Corsham an partake in a bit of vent-spotting to work the underground system out and fit the surface buildings and vent shafts to the maps of the underground I’d managed to get hold of. I knew people were still getting in, and so on each of these little walk rounds, I was always on the look out for fresh damage that might have been caused by some overly determined bunker vandal. Although I could find plenty of examples of historic abuse on these poor vent shafts, I never found anything that could have been of immediate use.

Keep digging

In any case, there had been a lot of talk about new alarms being fitted to some of the surface buildings and vent shafts outside the MOD perimeter fence (which didn’t really surprise me), so even if you could squeeze into one of the vents, there’d be a good chance you’d be setting the bells off and being booted into the back of a white Land Rover 2 minutes after getting inside. It was on one of these seasonal walk rounds with Keitei, that I figured a new approach would have to be taken. As I wasn’t really on for deploying the London can openers and teeing myself up for a few rounds of ‘MOD vs Barry Boltcropper et. al’ down Bath Crown Court, I figured the only option was to hop the fence and engage in a bit of Alsatian dodging for a closer look. Dressed like a pair of off duty soldiers, we scrambled over the barbed wire fence and went for a stroll around the live MOD base in broad daylight.

Not going to lie, I was absolutely kaking it.

We wandered round unhindered with squaddies jogging past us in gym gear (and getting one or two funny looks), slyly checking the surface buildings and emergency exits, most of which were locked tight or capped,

Blast! No Entry

Capped.

We were pretty much ready to leave, but I was keen to have another quick look at one of the remaining lift shafts. I didn’t have much hope to be honest when we got to the giant blast doors (overlooked by the biggest CCTV camera you’ve ever seen in your life), but on closer inspection, a bit of wriggling through a gap flung us out into an elevator room. The lift was obviously disabled and parked at the bottom of the shaft as we mashed the call buttons trying to shift it it with no luck whatsoever. Fair enough. We’d have to come back with some ropes.

2 hours later, and I was tying off on a fat I-beam, about to descend the lift shaft, deep into the bunker.

INB4 HATTONGARDEN, BITCHES.

I bloody hate zipping down live elevator shafts. All it takes is someone to press ‘up’ and before you know it you’re faced with a rapidly unfolding rope management disaster as the tangle you’ve spooled out below you wafts about close to the guide rails and counterweight. All it takes is a little nibble, and unless you can get to your Spatha in time to cut yourself free you’re gonna be crushed by your own harness against the top of the lift as it swallows your rope and rises to meet you. It’s hard to put this kind of stuff out of your mind, and even though the odds of people working in the underground on a Saturday afternoon were slim, it didn’t make it any easier.

All this disappeared when I touched down on the top of the dormant elevator. Through the small gap between the elevator car and the shaft, I could see a dim light and a tunnel stretching off into the distance.

Burlington.

I thought that was it, but after a further 20 minutes of scratting about, I realised I’d forgotten one crucial detail. Elevators only have ceiling hatches in movies, don’t they?

Fuck’s sake. I thought this was too good to be true.

The doors to the elevator had been left open, presumably to stop cheeky dickheads like me from calling it at the top and getting the luxury ride in, so I slid the doors shut from the top of the car and shouted to Keitei at the top to call the lift. Nothing. Maybe you need a key..?’

For the next three quarters of an hour I ferreted about the bottom of the shaft trying to get round this frustrating obstacle. I was a bit hesitant to touch the lift control panels at first after one or two OTIS emergency response alarms we’d caused after lift surfing in Manchester a couple of years previous, so if there was a way to just squeeze round the thing without interfering with any controls, it would have been preferable. Even after caking myself in 50 year old lift grease and getting down the sides of the thing I still hadn’t come up with anything. There was no panels in the top, bottom or sides that could have been opened, and the trellace doors on the other side had long since been sealed shut. The only way was to move the lift itself.

Back on top of the lift car, I started prodding some buttons. Nothing. The maintenance panel didn’t look super old, but it was certainly older than the ones I’d been used to messing about with on the lifts of the city’s tower blocks, but after another 20 minutes of this, I conceded the lift had been deactivated somewhere else and we would have to have a further think and jumared out. We left the base with our heads buzzing. How the fuckerdy split were we going to get past this lift?

Later on, at the mine party we’d travelled down to attend, I casually told a few people what we’d been up to. I honestly thought the Burlington hype was long over and that I was the only poor sod who’d missed it first time round, but when I mentioned, off hand, that I’d been stood on top of a lift shaft that afternoon with a three inch gap between me and the famous bunker, eyes lit up like bonfire night. ‘I wish you were telling the truth’… ‘If I ever got the call I’d be down there straight away’.. ‘I didn’t think it was doable any more..’

Just knowing that it’s possible is enough.

Both me and Katie had a few bits to do in the next week or so, but we agreed we’d convene in a fortnight and have another bash. My head buzzed over the next couple of weeks. How were we going to move that bloody lift? I transformed myself into a hardcore elevator design anorak, clawing for a weakness. Manual overrides, weaknesses in the panelling, construction diagrams and all the rest, until I came across an interesting document from the US Patent Office. I can’t remember what twisted vortex of hyper-links that got me to it, but in front of me was the original patent application to the exact lift controller we were trying to beat. Operational instructions, circuit diagram, optional alarm add-ons, even where to buy one if I wanted my own lift into my own super secret underground base.

That was it.

So back to Burly is was, and this time I’d given Morse a yell, a well seasoned lift surfer, who’d been with me for tonnes of those top-side walk rounds (even climbing the drainpipe into that derp farmhouse off Bradford Road looking for a secret escape hatch in the basement). Same deal, although feeling a bit more confident than last time, over a fence, waltzing through the base and squeezing into the elevator winch building (past some new building materials – they were obviously using the lift in the week) to abseil down the shaft where we found the lift sat in the same position, disabled with the doors open at the bottom of the shaft.

Even though we roughly knew what we were doing, it still took a good while to figure out the incantations and button combinations necessary to override the safety features and make the damn thing move. When the elevator car lurched into action and jolted upwards, I was grinning like a beaver.

One by one, we slid down the side of the lift, underneath the grease covered runners and out into the famous bunker.

WHAMMO.

We now had the place to ourselves, and with it being mid-day on a weekend, we had all the time in the world.

I’ll try and avoid getting too smushy, but there aren’t many places that give you the same feeling as being in Burlington, sans permission. The treacle thick gloom of cold war pessimism perforates everything. The utilitarian layout of the place glossed over with a desperate attempt to veil the unimaginable horror that would presumably be unfolding in the world above with a thin coat of British town life. The street names, a lovely canteen..

There has been quite a bit of work done down here since the last pictures I’d seen of Burlington made it into the public domain. Those funky little battery buggies were nowhere to be seen, and a lot of the lights had been removed making the photos a bit more of a test. The whole place was rather damp, although they seemed to be making a good effort in drying the place up with the tonnes of fans by most of the exits.

Dampington

Buggied out

all that was left

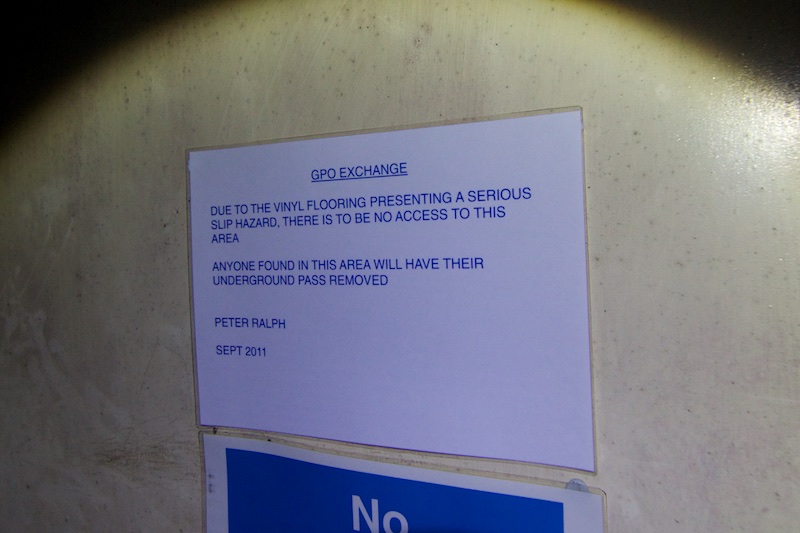

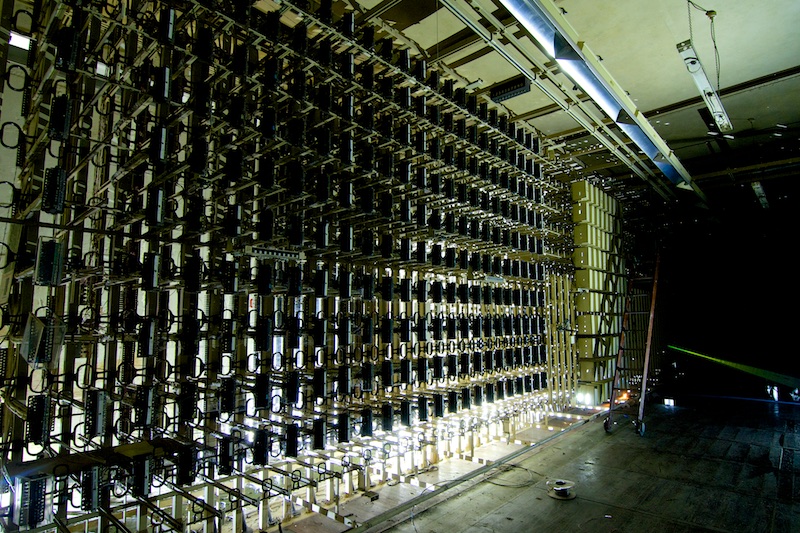

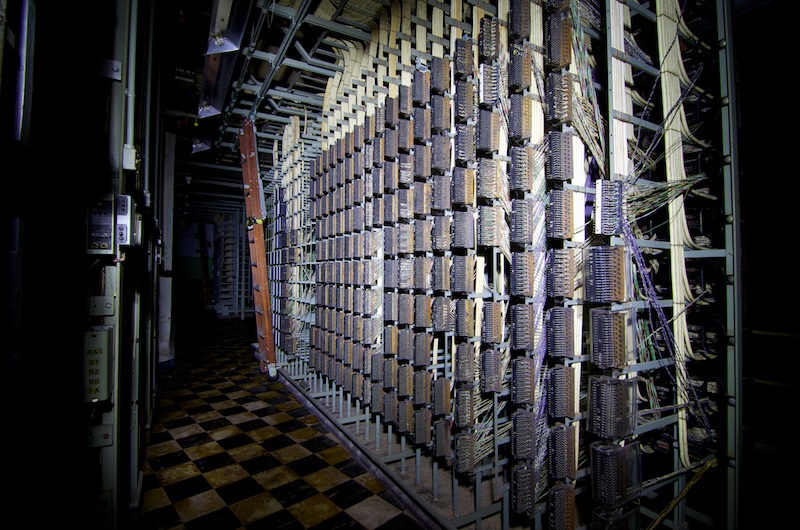

The first thing we wanted to have a goose at was the famed phone exchange, so off for a walk we went. It really pays to take a map down here, the place is bloody massive and mostly looks the same.

‘Was it this damp concrete tunnel or this one…. Or that slightly less damp, concrete tunnel back there…?’

There has obviously been some sort of incident down here in the past, some poor bricky pratting about with his mates must have taken a bit of a tumble. We ignored this sign, and as such, we’ve all had our underground passes removed.

Even the mainframe is still intact. Beauty isn’t it? I have no idea why it’s still here though, the value of copper in the thing must be worth absolute wedge.

Next stop.. Catering!

The canteen down here was big enough to keep the fires burning in the bellys of up to 4000 men and women for 3 months. It’s one of the biggest canteens I think I’ve even seen – they don’t make em like this any more.

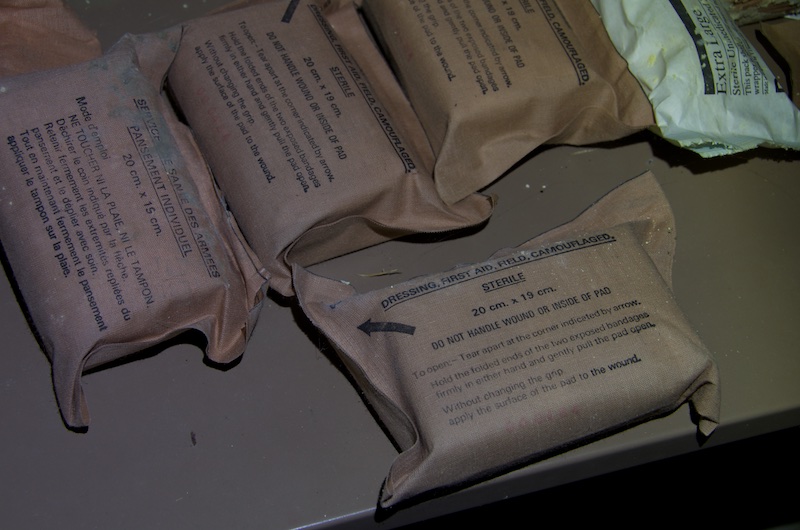

Boxes and boxes and boxes of slightly mouldy soap, bandages, note pads and cans of random stuff at the back end of the canteen. Smelt a bit fusty tbh. I’ve heard a few underground explorers say they’ll be heading to Burlington when the apocalypse comes, but it’s a shite idea in my opinion. It’s damp, all the food has been forklifted out or gone off, the drinking water lake has been drained and you’d have to spend the rest of your irradiated zombie-bitten days hanging out with a bunch of hairy urbexers. Don’t know about you, but I’m going to Scotland.

The drinking water lake. Collosal. Empty.

We had a good nosey round the old hospital, which is just as mouldy as everything else down here…

Hospital food

The other things on the hit list down here include the old school mega valve PA system which was presumably connected to miles of cables and hundreds of speakers dotted all over the facility (who’s yoinked one of those valves you wronguns?! – I’m telling Urbex Crimewatch).

The BBC studio was also a nice little feature, love all those retro acoustic panels. Bet its all going in the skip.

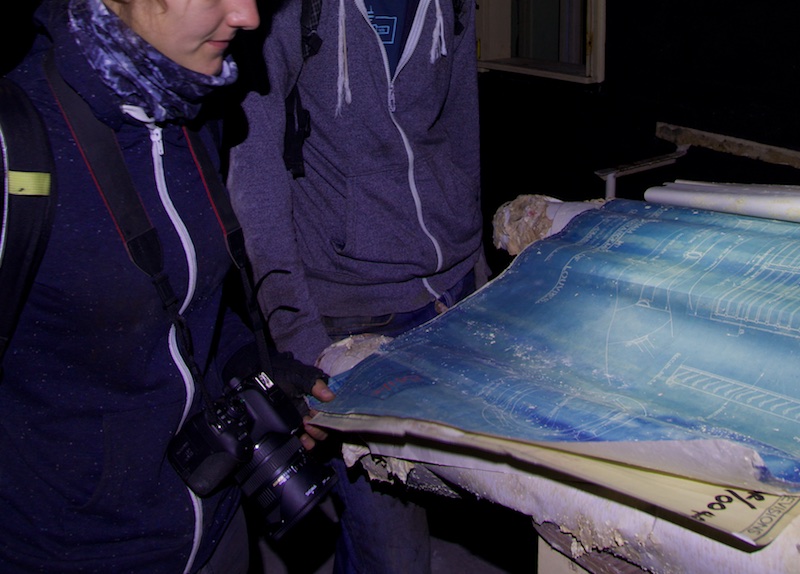

Next stop: Map Room.

Remember those ‘its nearly the end of the world’ scenes from the 70s Bond films where loads of fitties in uniform shoved little wooden counters around a big map while a load of concerned men in suits peered over from a set of elevated windows? This is the real damper, moldier version. Less maps, less sticks, less fitties.

They didn’t even have MSN Messenger in those days, so to shift information around the place, Burlington used a vast system on Lamson tubes. It’s basically a set of hoovers you put rolled up bit of paper into, which, though the miracle of air pressure, shoots your message to the destination written on the input tube.

borrowed from Keitei

Another cool little featurette down here is the mining museum. A big collection of rusty crap they presumably swept to one side when they were Brutalising the thing with concrete .

There are one or two little bits of pre-cold war heritage if you know where to look, but the vast majority of it lies in Spring quarry, just outside those battered red doors.

Here’s ‘tother side of one such door. Probably alarmed.

And here is the one into Tunnel Quarry. Locked :(

Interestingly, most of the other lifts were cream crackered, so the one we came down must have been the only one left working.

There were a few other nice little curiosities, the famed London Underground escalator (now just a staircase)

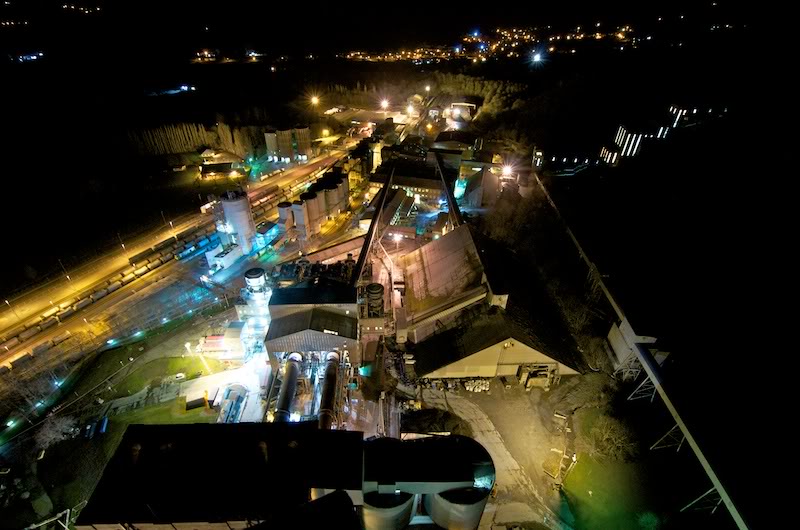

And the mammoth ventilation systems – didn’t get enough photos of all this stuff – was getting a bit tired by then I think.

But by this time, we’d pretty much had our fill and it was high time for leaving.

We’d been down there god know how long and I was thirsty for a couple of jars at the Quarrymans’. It was a truly amazing place to see, but damn, Clement Attlee, what a waste of money.

We slipped back into that god forsaken lift and climbed on top, surfed out and put everything back the way we found it.

I don’t know why we bothered though, we told a few mates…

.. and they told theirs, and they told theirs, and somewhere along the way, someone didn’t put it back the way they found it.

The cycle continues.

Next level adventure and writeup!

That place is probably stuffed full of asbestos…

Keeping it real as fuck.